The plan to build an 85-acre police training site in Atlanta has ignited a diverse movement of people hoping to protect their communities.

Atlanta officials are pushing ahead with a sprawling, $90 million public safety training center, colloquially known as “Cop City,” that opponents say will damage the environment, militarize the police and put civilians in harm’s way. Amid the ongoing struggle, law enforcement officers have killed at least one protester and charged dozens of people with domestic terrorism.

The sheer size of the training center has drawn critics, who see it as a threat to the community. Opponents of the project have organized protests and experienced numerous confrontations with police, dating back to 2021. Some activists have even moved into the forest where the center is planned to be built, living in encampments as part of their protest. Others are hosting learning seminars, going door to door to raise awareness of the issue or sharing information online, many using hashtags like #StopCopCity or #DefendWeelauneeForest.

Multiple organizers described the movement to HuffPost as autonomous and decentralized, meaning no one person or organization is calling the shots. Instead, a variety of communities — including Black people, Indigenous people, environmentalists and abolitionists against the prison-industrial complex — are joining together with the same goal: to stop Cop City from being built.

A Training Site On ‘Critically Important’ Land

The facility is set to be built on land that’s been deeply intertwined with the plight of Black and Indigenous people for centuries.

The Weelaunee Forest, currently known as South River Forest, belonged to the Muscogee Creek Nation until the 1820s and ’30s, when white settlers violently pushed them from their land, leading to thousands of deaths in the process.

During the 20th century, part of the forest was turned into the now-abandoned Old Atlanta Prison Farm, where officials subjected prisoners, especially Black ones, to torture, malnutrition, slave labor and sexual violence for decades.

Despite its complex and dark past, the land now offers a space of community, with a bike trail, a lake, a rock garden, a cemetery, multiple parks, a golf course, a sports complex and more. It was dubbed one of the four “lungs of Atlanta” in a report from the Department of City Planning, and was supposed to be protected against commercial and residential development to preserve its environmental benefits, according to the Nature Conservancy.

“The ecological benefits ― such as floodplain restoration, habitat expansion, and tree canopy protection ― are critically important to Atlanta’s future in the face of a population expected to triple in size by 2040,” a post on the Nature Conservancy’s website said of the land.

In September 2021, Atlanta’s city council voted in favor of the training site despite having heard 17 hours of comments over a two-day span, primarily from people who disapproved of the project.

“Everybody was floored,” Jacqueline Echols, board president for the South River Watershed Alliance, told CNN the following year. “Just in 2017, they’d said this would be a park and a community investment.”

What Is Cop City?

According to the Atlanta Police Foundation website, the Atlanta Public Safety Training Center will “reimagine” training and community engagement for police and fire rescue.

The center would be larger than the police training academies in the country’s two most populous cities — more than four times the size of the 20-acre Los Angeles Police Department training campus, and more than 2.6 times the size of the New York Police Department training academy, which measures 32 acres.

This is despite the fact that the LAPD and NYPD “have significantly larger police forces than Atlanta,” Hannah Riley, an organizer involved in the Stop Cop City movement, told HuffPost.

The center, according to the police foundation, will aim to “improve morale, retention, recruitment and training for [Atlanta Police Department and Atlanta Fire Rescue Department] professionals and ensure that Atlanta attracts and motivates those most highly committed to careers in law enforcement.” It will also aim to “set a national standard for community engagement, neighborhood sensitivity and devotion to the civil rights of all citizens by law enforcement,” the foundation says.

The nickname “Cop City” points to the plan to build a mock city where authorities would be able to train for conflict. The facility also has plans to house a military veteran training center, a shooting range, a horse barn and a nature trail, among other features.

The Atlanta Police Foundation is leading the endeavor to build the center, providing $60 million worth of funding. An additional $30 million is expected to come from taxpayers.

According to CNN, the Atlanta Police Foundation generates more revenue than any of the 150 police foundations in other municipalities whose data CNN reviewed. Police foundations can aid official law enforcement departments by operating outside of political and financial limitations that departments would face, CNN notes.

The Atlanta Police Foundation has helped that city, which is nearly 50% Black, become the most surveilled in the U.S., according to Atlanta magazine.

The Color of Change, an online racial justice organization, and Little Sis, a watchdog database that focuses on business and government, published an extensive report that looks at data and research on how police foundations are funded and how their spending targets communities of color.

“The kind of surveillance and militarized equipment funded by police foundations are increasingly used against protesters seeking to end policing’s abuses in what the New York Times has called the largest sustained mobilization in U.S. history,” the report reads. “While it is estimated that the majority of demonstrators are white, reviews of arrest records the weekend after George Floyd’s murder, where available, show that those jailed were disproportionately Black: 70% in Chicago and 60% in Atlanta.”

When contacted by HuffPost, the Atlanta Police Foundation declined to provide comment.

In April 2021, Keisha Lance Bottoms, then the mayor of Atlanta, made public the plans to build the new training center. It had been less than a year since the 2020 murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis ignited historic nationwide uprisings in opposition to police violence. Less than three weeks after Floyd’s murder, Atlanta police officers killed a 27-year-old Black man named Rayshard Brooks.

“There were uprisings across the nation in defiance of state violence and state-sanctioned killing, especially with Black people. And that had been the case in Atlanta as well,” Riley told HuffPost. “Folks were out in the streets in the summer of 2020. There was a ton of anger and hurt surrounding the murder of Rayshard Brooks.”

Bottoms did not immediately respond to HuffPost’s request for comment.

“There is a great deal of misinformation about this site,” Bryan Thomas, the communications director for the city of Atlanta, told HuffPost. “There is no military type training at the site,” he added.

“I like to remind people that Garrett Rolfe, who is the APD officer who killed Rayshard Brooks, had just undergone de-escalation training and some other training ― the types of things that reformists would point to and say, ‘Well, here’s what should have happened,’” Riley said. “And so we know that training does not mean that police become less violent or deadly, or that they surveil us less. It typically means that they get better at it.”

Cop City, Riley says, would further entrench police “as this occupying military force in our neighborhoods who are not there to keep us safe, but to keep us in line through violence if necessary.”

The Death Of An Activist

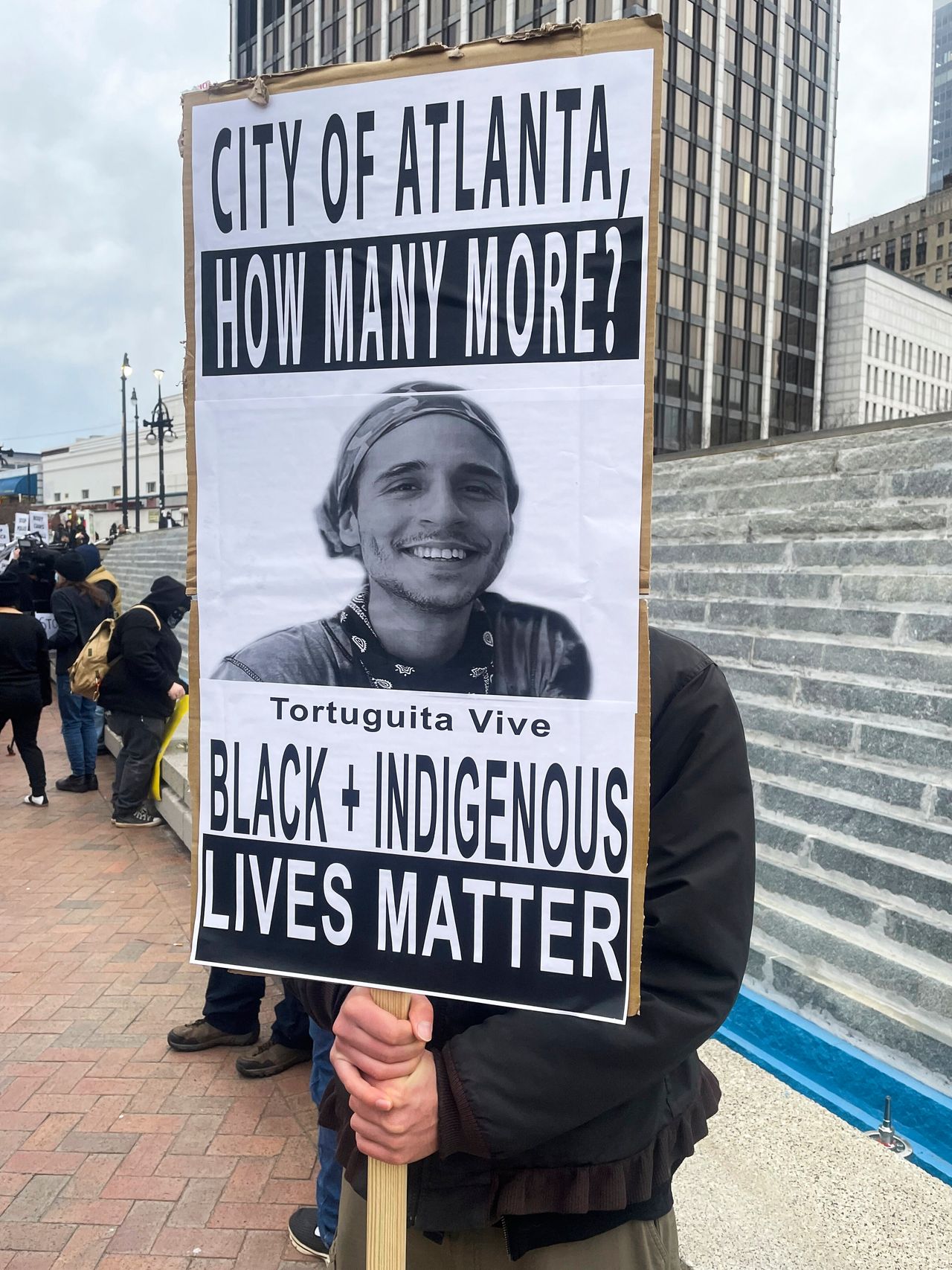

“Am I scared of the state?” a nonbinary activist known as Tortuguita, born Manuel Esteban Paez Terán, asked the Atlanta-based news outlet The Bitter Southerner in a December 2022 article. “Pretty silly not to be. I’m a brown person. I might be killed by the police for existing in certain spaces.”

Georgia State Patrol officers fatally shot Terán more than a dozen times during a raid the following month. Terán was likely sitting on the floor with their legs crossed and their hands raised, according to an independently performed autopsy published by the independent media outlet Unicorn Riot. (The first autopsy, conducted by the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, is not currently available to the public.) Terán was 26.

The late activist was a “forest defender,” part of a group of people living and spending time in the forest as an act of protest and in an effort to stop Cop City from being built.

While authorities initially said that Terán shot an officer, their story has changed multiple times.

Audio from Atlanta Police Department body camera footage suggests that an officer may have been shot by friendly fire, not by Terán ― a point that activists have been articulating since Terán’s death. No gunpowder was found on Terán’s body in the independently conducted autopsy, which could indicate they did not shoot a gun at all.

Terán’s killing may mark the first time an environmental activist was killed by authorities in the United States, according to The Guardian. Their death has led to widespread outrage and media attention.

A Persistent Movement

Despite Terán’s death and a surge in charges against protesters, the #StopCopCity movement has persisted.

“It’s hard to say what would’ve happened otherwise [if Terán hadn’t been killed], but I can say that the movement is as strong and as vibrant as it’s ever been,” Sean Wolters, an organizer with the Defend the Atlanta Forest movement, told HuffPost. “There’s still a lot of undeterred people who are thinking through how we can continue to fight to defend the forest and stop Cop City.”

Last month, more than 100 protesters raided the site wearing all-black clothing. The protesters threw rocks, bricks, Molotov cocktails and fireworks, destroying equipment, according to ABC News. No officers were injured, but 35 people were detained and 23 were charged with domestic terrorism, a felony offense that can carry up to 35 years behind bars.

On the day Terán was killed, seven people were arrested and charged with the same offense. Five others were arrested and charged with domestic terrorism in December.

Riley, the Stop Cop City organizer, said there is a “clear political motivation” to the charges.

“Despite the increased intimidation and harassment and suppression, the movement is emboldened. It is not going anywhere,” Riley said. “People see this for what it is. They see that it is an attempt to squash people’s First Amendment rights to free speech and to dissent from terrible things like this.”

Conservative outlets like the Daily Mail and Fox News have lumped all the different facets of the movement together as “Antifa,” and city officials have described opponents as “outside agitators” ― a term that can be traced back to at least the Civil Rights Movement, and that aims to discredit locally driven protest efforts.

Atlanta-based organizer Micah Herskind told HuffPost that some news outlets and city officials are sticking with the narrative “that burning machinery and destroying equipment is violence.”

“Of course,” Herskind said, “actual violence and harm that the police do against people every day, that will be amplified by Cop City, is somehow completely erased from the narrative.”

The Case For Abolition

Abolition is a principle at the center of the fight over Cop City, according to community organizers who oppose the project.

“I come to it from sort of an abolitionist angle, recognizing that policing doesn’t make people safer, and it in fact causes a lot of harm in our communities,” Herskind told HuffPost.

Though approaches vary, abolitionists typically want to dismantle old systems and replace them with newer, better ones that mitigate or prevent harm rather than exacerbating it. Sometimes this involves imagining solutions that haven’t been created yet.

“Using police and punitive approaches as the primary tools to address health and social issues including mental illness, substance use, homelessness, community violence and poverty funnels millions of people into jails and prisons,” the website of the Vera Institute of Justice reads. “Other investments would support communities in prospering and do not come with the substantial social costs and harms that accompany positioning public safety as exclusively the domain of law enforcement.”

Some abolitionists speak of community patrols, investing in mental health services and pursuing restorative or transformative justice in place of the existing prison-industrial complex.

In the abolitionist perspective, current aspects of society like excessive policing and a faulty criminal justice system, as well as the dangers and destructive effects of prisons, are ultimately unhelpful because they don’t actually break habits or prevent harm.

And many abolitionists regard policing, with its roots in white supremacy, as something that can’t be reformed, but needs to be dissolved.

By contrast, many lawmakers and other officials argue that policing ensures community safety, although there is no correlation between police spending and crime rates.

Angela Davis, a prominent abolitionist activist, has made it clear that she stands in solidarity with the effort to stop the training center in Atlanta from being built. She even returned an award that the city council gave to her in March.

If the training center is built, “this will represent a major setback for the movement for radical democratic futures ― not only throughout the U.S., but globally as well,” Davis said in a video statement on April 1.

Davis went on to applaud the activists in Atlanta and the multipronged movement they’ve pushed forward.

“Atlanta activists are on the front lines of the abolitionist movement at its crucial intersection with movements to save our forests ― indeed, to save our planet,” Davis said. “This is an especially important time to speak out simultaneously against organized police racism and repression and the destruction of our planet.”

Terán, whose killing Davis condemned in her statement, also identified with the goal of abolition.

“The abolitionist mission isn’t done until every prison is empty,” Terán told The Bitter Southerner in December. “When there are no more cops, when the land has been given back, that’s when it’s over.”

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story stated incorrectly that the Atlanta facility would be the country’s largest police training site. In fact, at least two other sites in the U.S. are larger.